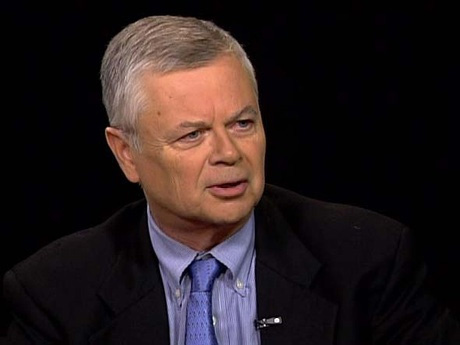

Kinzer: Shah was difficult to sustain by democratic society

Saman Safarzaei

Kinzer is also a writer and has spent more than 20 years working for the New York Times, most of it as a foreign correspondent. His foreign postings placed him at the center of historic events and, at times, in the line of fire. While covering world events, he has been shot at, jailed, beaten by police, tear-gassed and bombed from the air. Before joining the New York Times, Kinzer was a Latin America correspondent for the Boston Globe. Kinzer contributes articles to the New York Review of Books and other periodicals, and writes a world affairs column for The Guardian.

He is also the author of “All the Shah’s Men: An American Coup and the Roots of Middle East Terror.”

This interview was originally published as a Persian translation by Tarikh Irani (Iranian History).

IH: Dr. Kinzer, in the book “All the Shah's Men” you provide interesting information about the Safavid Shi’a Islam. The role of the Shi’a Islam in victory of the 1906 Iranian Constitutional Revolutions has been highlighted in your book. How do you see the role of the Shi’a Political Islam in victory of 1979 Revolution? There was a broad coalition of forces such Marxist, liberal intellectuals, the urban middle class which had been mobilized against the Shah. How much was the presence of Shia Islamists vital in this coalition? Do we have to accept the idea which insists the Iranian was not able to overthrow the Shah if there was no Shi’a ideology?

SK: The Shi’a view of life stresses the right of all people to justice. It does not stress submission to authority or the state. This makes a Shi’a population more difficult for regimes to control. There was a widespread sense in Iran that the Shah's regime was unjust, and this certainly contributed to the emotions that exploded in 1978-9.

IH: I guess you believe that the 1953 coup had a large role in raising the anti-American feelings among Iranian revolutionary movement from 1978- 1979. But when we look back at the years and decades after the coup, in particular Pres. Kennedy and then Pres. Carter pressured Shah to end his policies violating the human rights of Iranian. Why did not these American pressures on Shah help the protesting movements of Iran in 1978 to forget the dark past policies of U.S against democratic state of Dr. Mossadegh?

SK: Kennedy's view did lead to some changes in Iran, but he was not in office long enough for it to have a deep effect. Carter's view toward the Shah was complicated. He seemed to realize that the Shah was a bad man, but believed he could be transformed into a good man. This led to a confused policy.

IH: In the 1970s, the true political followers of Mossadegh, such Bazargan, Sahabi and Sedighi, basically did not carry any anti-American feelings and did not ask the society to revolt against American values. On the other hand, the Islamists which really did not like Mossadegh and his democratic state had very large anti-Western feelings. In fact how come the social movement which was angry about the 1953 coup did not follow the views of its real political leaders? How could you explain this paradox?

SK: Mossadegh was a great admirer of the United States. So were most Iranians. There is no automatic anti-Americanism in Iran, as there is sentiment against Britain. In fact, I believe that the people of Iran today are more pro-American than the people of any other country in the world. When I visit I am surrounded by people telling me how much they love America. They have not forgotten the 1953 coup, but they have moved past it. Perhaps they see in the United States a level of prosperity and openness that they wish for in their own society.

IH: In the case of Iranian revolution, when did the Carter administration decide to ask the Shah to leave the power? Since when the American Democrats came to the conclusion that the protest movement of Iran is in an irreversible point? Did they understand the revolution at the right time or was it late?

SK: Many Americans believed then what many Iranians also believed: that no matter what came after the Pahlavis, it would be something better. The revolution was made by people from a wide spectrum of society and with various political beliefs. It was not clear at that time which group would emerge as dominant.

IH: Do you think the structural and political aspects of the regime of Shah were on the verge of collapse, and the falling was inevitable, and that the Islamic Revolution in 1979 only accelerated the gradual collapse? Or do you believe that rising oil prices and increasing military power and position of regime in Middle East were such that signs of the fall of regime were not seen in the timeliest manner?

SK: A repressive regime like the one the Shah directed is hard to sustain in a country where people understand democracy. The Shah's policies also contributed to his downfall. The reforms of the White Revolution created a huge class of people who left the land and poured into cities. The economy could not support them. A combination of rising expectations, poor government, and repression produced the explosion.

IH: What do you find the most important feature of Shah's regime to promote and spread the demonstrations and ultimately help the revolution? In other words, what were the characteristic in this regime which led to the choice of overthrow?

SK: The Shah crushed every avenue for peaceful protest. Civil society was repressed. There were no real opposition parties or labor organizations or professional guilds or farm groups. Everything had to be subservient to the regime. The only place where the Shah tolerated dissent was in the mosque, which he did not dare to attack. When people in a country like Iran find that peaceful avenues toward change are closed, revolution becomes an option.

نظر شما :